KIm Them Do

Reza Pahlavi and Iran: A Future Beckoning—or a New Storm Beginning?

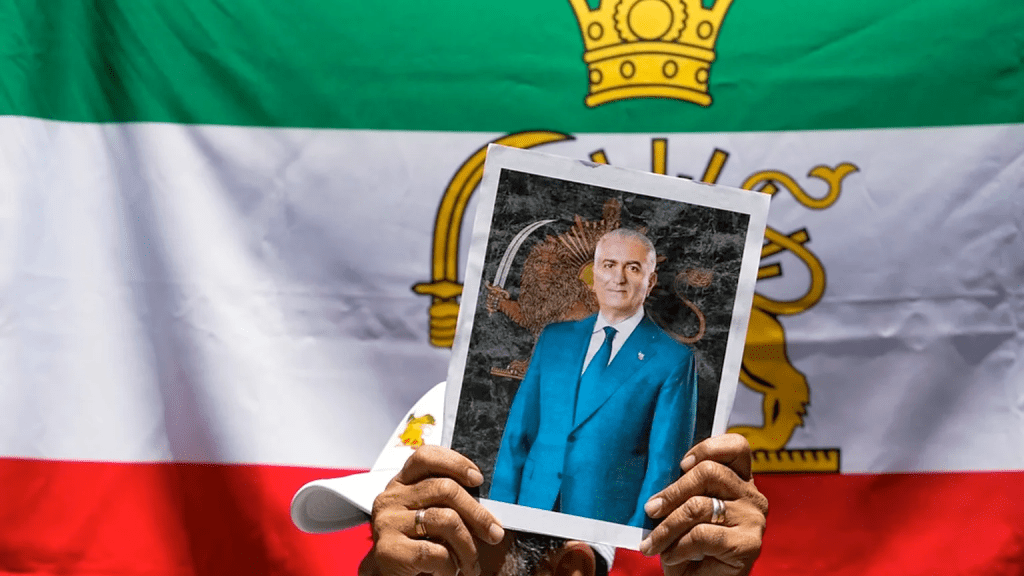

Protests against Iran’s theocratic system continue unabated. Notably, this latest wave of unrest has been accompanied by public calls for Reza Pahlavi—the son of the Shah who was overthrown in 1979 and who has since lived in exile in the United States—to return to Iran and assume a leadership role. Almost overnight, Reza Pahlavi has become a prominent figure in Iran’s turbulent political landscape, presenting himself as a representative of the Iranian opposition abroad.

Calls to replace what protesters describe as the “shameful flag of the Islamic Republic” with the pre-revolutionary monarchical flag at Iranian diplomatic missions abroad have attracted significant attention, both domestically and internationally.

This raises a crucial question: what role, if any, can Reza Pahlavi play in restoring social and political order today? Can his appeal meaningfully contribute to transforming the Islamic Republic—or even take Iran beyond the political framework that existed prior to the 1979 Revolution?

Reality suggests that the past cannot simply be revived. Iranian society has changed profoundly. Today, the Iranian people appear less interested in restoring a monarchy than in ending the Islamic Republic and overcoming the heavy legacy left by the 1979 Revolution.

Iran Before 1979

After the 1953 coup—backed by the United States—which overthrew the democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi ruled Iran as an increasingly unchallenged autocrat.

Beginning in 1963, through the so-called White Revolution, the Shah sought to modernize the country via land reform, expanded education, labor initiatives, and suffrage for women. However, these reforms failed to produce their intended outcomes and instead intensified social tensions. Large landowners were generously compensated after dispossession, while many farmers fell into debt and struggled to sustain themselves through agricultural production. As a result, economic inequality widened and social unrest deepened.

Confronted with growing dissent, the Shah increasingly focused on preserving his regime through repression. Iran lacked free elections, political opponents were persecuted, tortured, or killed, and dissent was systematically silenced. Over time, the country’s development trajectory deteriorated into that of a totalitarian police state.

Khomeini and the Islamic Republic

As early as the 1960s, the cleric Ruhollah Khomeini—an Ayatollah and scholar of Islamic law—openly opposed the Shah’s policies. During his exile in France, he developed plans for a theocratic system that fused political authority with religious doctrine.

At the time, much of the Western media viewed Khomeini sympathetically, portraying him as a moderate figure capable of guiding Iran toward democracy and independence. This image gained widespread support among those opposed to the Shah.

By the mid-1970s, declining oil revenues rendered state-led development programs unsustainable, exacerbating public dissatisfaction. Nationwide protests erupted to which the government responded with military force. At the same time, religiously motivated violence increased, including attacks on cinemas and liquor stores.

Mass protests and strikes ultimately eroded the Shah’s authority, forcing him to leave Iran in early 1979. On April 1, 1979, Khomeini returned and proclaimed the Islamic Republic of Iran.

The Islamic Revolution of 1979

The overthrow of the Shah enjoyed broad support across Iranian society, including religious groups, intellectuals, students, and left-wing organizations. This moment of national unity was driven by two primary factors: widespread opposition to the Shah’s authoritarian rule and strong resentment toward U.S. interference in Iran’s internal affairs.

Many Iranians believed that the Islamic Revolution, combined with the establishment of a democratic system, would secure a prosperous future. Aware of these expectations, Khomeini initially avoided openly advocating for the enforcement of Sharia law or mandatory veiling for women. Instead, he fueled popular hopes by promising democracy, freedom, and the rule of law, along with social welfare measures such as free electricity, fuel, and oil for the population.

Current Protests

Over time, many of those who supported the Islamic Revolution of 1979 have grown deeply disillusioned with its original promises. Instead of the democratic, free, and secular state that many once anticipated, they have witnessed the emergence of yet another dictatorship—this time legitimized in the name of the Islamic Republic—amid persistent and deepening social unrest.

The Iranian political system is fundamentally rooted in religious authority. Its central pillar is the doctrine of Velāyat-e Faqīh (Guardianship of the Jurist), which grants supreme political power to the Shiite clergy. Since 1989, this authority has been embodied by Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who, under the Iranian Constitution, holds ultimate decision-making power in both political and religious affairs. He also serves as Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. For decades, this clerical elite has preserved its dominance through extensive and systematic repression.

In recent years, public criticism of the Islamic Republic has become increasingly explicit, particularly regarding women’s rights, social justice, and economic inequality. A sustained cycle of protest began in 2017–2018, marking the first time that segments of the population previously loyal to the regime openly joined demonstrations. This was followed by nationwide protests in 2019 and a major uprising in 2022–2023, in which women played a central and defining role.

The current wave of protests erupted in December 2025, triggered primarily by a severe economic crisis. The national currency rapidly depreciated, inflation soared, and the cost of living became unbearable for large segments of the population.

Taken together, this constitutes the fourth major uprising in less than a decade. The intervals between protests are shrinking, while both their scale and the diversity of participating social groups are expanding. This pattern suggests not merely another episode of unrest, but potentially the final phase—or at least a direct precursor—to the collapse of the Islamic Republic. The regime increasingly appears to be entering its final countdown.

Unlike earlier movements, today’s protests directly challenge the legitimacy of the Islamic Republic itself. In doing so, they force Iranian society to confront fundamental questions about the political order established by the 1979 Revolution.

At the core of the current unrest lies widespread dissatisfaction with the ruling system. The state is no longer capable of guaranteeing social security or providing even minimal economic stability. Instead, government policies primarily serve the interests of a narrow ruling elite. While much of the population struggles with poverty, national resources are consumed by an expansive political and religious apparatus—one designed to sustain repression, suppress democratic participation, disregard human rights, and offer no credible vision for social or economic development.

The Role of Reza Pahlavi

Against this backdrop, domestic and international media have increasingly focused on Reza Pahlavi—the son of the Shah overthrown in 1979 and a longtime exile in the United States—who has presented himself as a representative of the Iranian opposition abroad. He has called on citizens to occupy urban centers and declared his readiness to return to Iran to stand alongside the protest movement. These statements have attracted millions of followers on social media, while simultaneously generating intense controversy.

Supporters argue that Reza Pahlavi could serve as a unifying symbolic figure for the fragmented opposition and help mobilize international attention, even if they do not necessarily advocate for the restoration of the monarchy.

Critics, however, question his practical political capacity. He has yet to articulate a coherent political program or establish a durable organizational structure. During the “Women, Life, Freedom” movement three years earlier, he failed to unify opposition groups in exile; instead, ideological divisions persisted and, in some cases, deepened.

Today, Reza Pahlavi is undeniably a visible actor in Iran’s evolving political landscape. Yet while Iranians inside the country have a clear objective—ending the current regime—they largely reject both alternatives associated with the past: the re-establishment of monarchy and the reform of theocratic rule. Although visions for Iran’s future are diverse, they remain fragmented and insufficiently defined.

The realities of Iranian politics further limit Pahlavi’s influence. He lacks a robust organizational base, has no meaningful alliance with the military, state institutions, or economic elites, and commands no decisive loyalty among key power brokers. Decades of exile have distanced him from domestic political dynamics and constrained his ability to fully grasp the social realities on the ground. Moreover, he has been unable to form a viable alliance with religious actors—still a crucial component of Iran’s power structure.

As a result, Reza Pahlavi’s role is likely to remain confined to external advocacy and symbolic influence rather than direct leadership from within the country. Without a substantive political institution, any attempt to restructure Iran’s political, economic, and security systems would face severe structural obstacles.

In this sense, the current protests reveal a more fundamental truth: the Iranian people seek to break free from the entire political legacy of the 1979 Revolution—encompassing both theocratic rule and the prospect of monarchical restoration.

Whether the regime in Tehran will be overthrown in this phase remains impossible to predict. Even in a scenario where the Supreme Leader and senior clerical authorities lose power, the ideological and institutional foundations of the theocracy are likely to endure. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, functioning as a “state within a state,” may further consolidate its influence in the absence of a credible alternative. After nearly half a century, the theocratic system has become deeply embedded in Iran’s political culture and social consciousness.

Consequently, a genuine process of secular democratization has yet to begin, and the restoration of social stability will be extraordinarily difficult. The emergence of a new military-backed authoritarian order cannot be ruled out. If a credible and inclusive political alternative fails to materialize, Iran may soon find itself confronting yet another profound political storm.